The Conquest of Reasonably Priced Bread: Food Inflation in Japan

Japan has seen rapid food inflation over the last 12-month period, witnessing growth to a 7-year high of 4.1% in May 2022 year on year. Upward pressure has not been consistent across the board- fresh vegetables and seafood has seen YoY inflation of 12.3% and 9% respectively, while meats and dairy rose in price 2.7% and 1.1%. Cooking oil has also seen inflation of 6.3%. Overall, while some prices have stayed low, the cost of food staples for the Japanese people have increased by over 10%. Apart from the anomalies discussed below, food cost increase in Japan is equivalent to other developed economies.

As a country who has experienced price freezes and deflationary cycles since the asset bubble collapse of 1991, the current situation of rising prices has been a shock amongst consumers. Rising supply expense has meant food manufacturers are taking the rare step of defraying excess costs by passing them on to buyers. Post-1991 Japan has become particularly price conscious, and food inflation is now a major political issue.

From a macro perspective, Japanese food inflation can be broken down into three main causes:

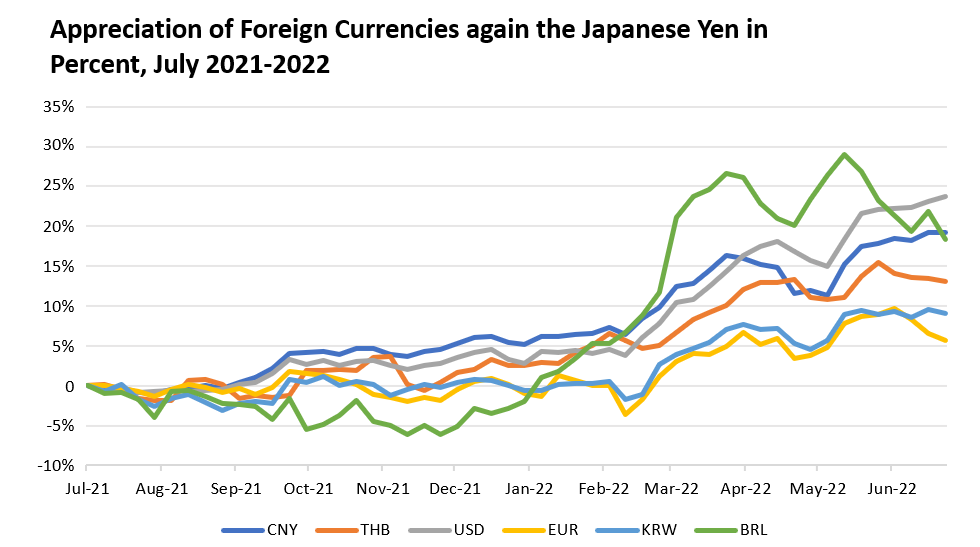

- A weak Yen. As of 7/8/22, USD/JPY is sitting at 136.17, the strongest the dollar has been versus Japan’s currency since 1998. Japan is the least food self-sufficient country in the G12, and by the latest data from the Ministry of Agriculture it imports 60% of agricultural needs. It also depends on imports for 94% of its energy supply. Unfavorable exchange rates have made bringing in food more expensive from foreign countries than in previous periods, as consumers are forced to pay more for equivalent goods.

The frailty of the Yen has come as most other global economies have adopted a policy of quantitative tightening and interest rate hikes to combat inflation, while Japan has kept rates ultra-low at a benchmark of -.1%.

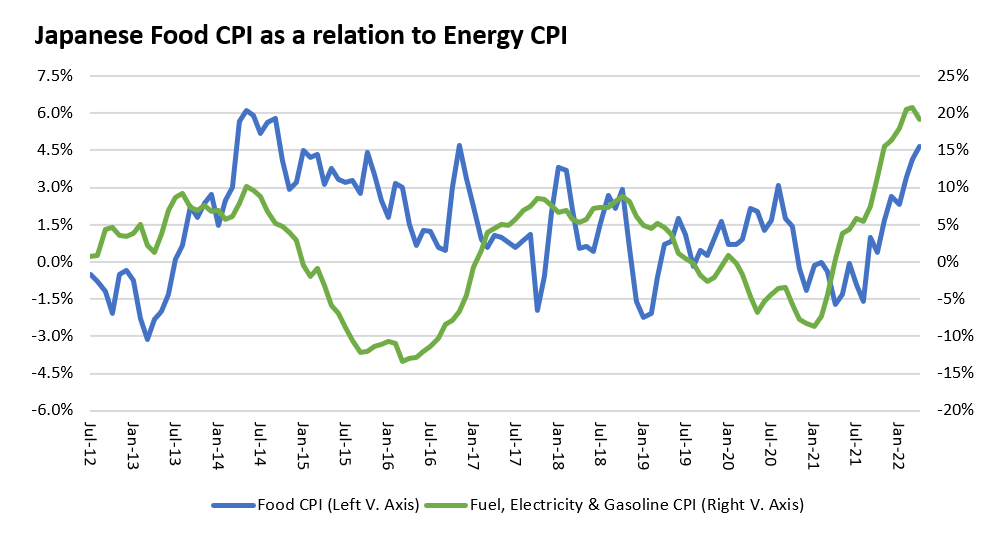

- High energy costs. Energy and food prices are tied at the hip- especially so for import dependent countries. Compounding upon unfavorable forex rates, increased fuel costs have a dramatic factor in increased food prices. The graphic below shows this correlation- notice the time lag between the change in curves of the two indexes.

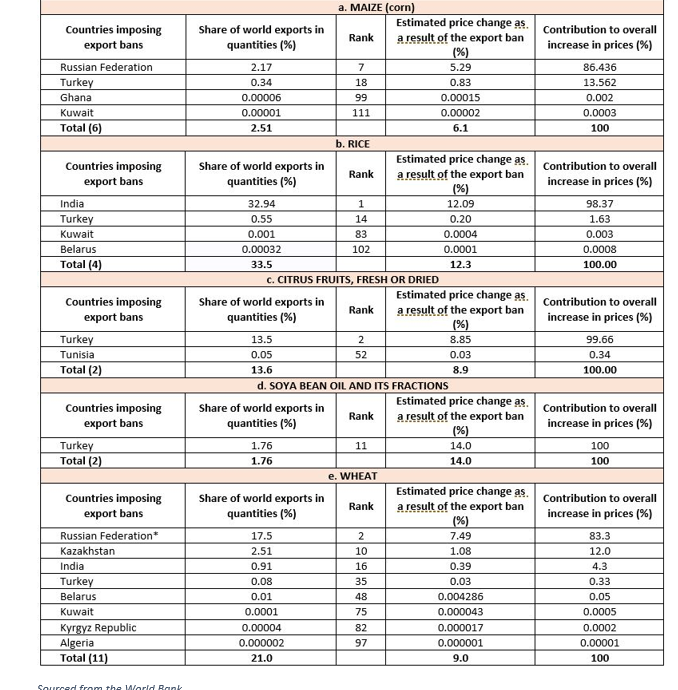

After arriving in country, transportation from shipping hubs to grocery stores has also been severely affected by fuel inflation. As a metric, it is estimated by the USDA that a 1% increase in diesel price incurs a .20-.28% increase in prices of wholesale produce. - Supply chain slowdowns and shortages. Perhaps the biggest factor contributing to inflating food prices in Japan and globally are difficulties in exporting food in the first place. Many of the world’s biggest producers of agricultural products are affected by the Ukraine conflict, which has directly resulted in the inflation of cooking oil, onions, and wheat.

This has had a knock-on effect for countries who export to Japan. Many such as India, Malaysia, Indonesia and Argentina in the face of rising prices have wholly banned sections of their food industries from exports. Others have placed heavy restrictions on items sold overseas. These embargoes have closed off major markets servicing Japan’s food needs and forces the island nation to compete against other countries for a stake from a dwindling number of exporters.

However, many important food industries in Japan have not seen major inflation. Meat, dairy and meals outside the home have seen prices increases well below the rate of other developed countries. Below I will discuss my findings on these outliers.

Dairy: While the cost of dairy products wholesale has increased 38% YoY in the U.S., it has remained virtually stagnant in Japan. The lack of inflation in the dairy industry is due to one primary reason- rather than a free-market system to determine price, an association of Japanese dairy farmers and manufacturers meet annually to set cost guidance, which is not altered intra-year. This has resulted in farmers being unable to defray the cost of rising animal feed prices on consumers and have been left with no choice “but to deal with it”, as NHK reports. Dairy producers have petitioned wholesalers to increase the price at which they buy product, but that proceeding as of the time of this writing has not reported value changes.

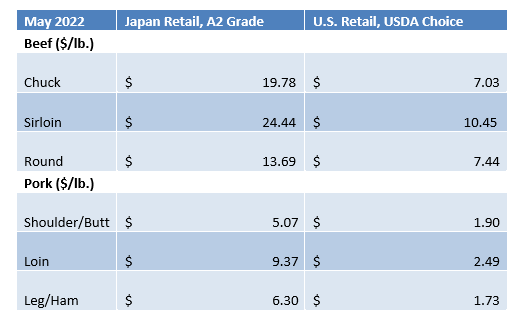

Meat: This in particular was a difficult question to resolve. Meat livestock, like dairy, is similarly affected by the rising costs of animal feed and there is no price control for the product in Japan. The country also imports 72.3% of its beef and 54.2% of its pork- exposing the industry to trade difficulties. I attribute the lack in price movement to the high premium meat is already sold for. The price of meat products in Japan is 98.6% higher than the global average. This is in comparison to other developed countries like the U.S. (25.6%), Germany (29.2%) and Australia (40.7%). Below is a table demonstrating the price disparity- this leaves retailers in Japan with greater room to soak up rising supply expenses.

Restaurants: The prepared food industry has historically been a symbol of Japan’s stagnation. Decades of anemic growth have made Japanese consumers extremely price sensitive, and there has been reluctance amongst restauranteurs to pass on the higher supply costs they face. Tsutomu Watanabe, an economics professor at Tokyo University, says, “the psychology of the Japanese public does not allow for even a tiny increase in prices”.

For this reason, May CPI reports prices of meals away from home have remained largely. However, as supply problems are seen to persist, attitudes are changing. Pre-prepared food prices will see inflation- 3/4 of Japanese restaurants have announced plans for price increases in the second half of 2022.